Chapter 29

Uveal Effusion Syndrome

Uveal effusion syndrome (UES) is a rare syndrome of idiopathic exudative detachments of the choroid, ciliary body and retina. UES was first described by Schepens and Brockhurst in 1963.[1]

There are three types of Uveal effusion syndrome:[2]

- Type 1 - Nanophthalmic eyes (average axial length 16 mm)

- Type 2 - Non-nanophthalmic eyes with clinically abnormal sclera

- Type 3 - Non-nanophthalmic eyes with normal sclera

This frequently bilateral syndrome most commonly occurs in middle-aged men, but there are reports in the literature of unilateral cases and patients as young as 11 years old.[3]

Schepens CL, Brockhurst RJ. Uveal effusion 1. Clinical picture. Arch Ophthalmol. 1963;70:189–201

Uyama M, Takahashi K, Kozaki J, Tagami N, Takada Y, Ohkuma H, Matsunaga H, Kimoto T, Nishimura T. Uveal effusion syndrome: clinical features, surgical treatment, histologic examination of the sclera, and pathophysiology. Ophthalmology. 2000 Mar; 107(3):441-9.

Casswell AG, Gregor ZJ, Bird AC. The surgical management of uveal effusion syndrome. Eye.1987;1:115-119.

There are several theories regarding the pathogenesis of UES such as: increased choroidal permeability, intrinsic choroidal alterations, vortex vein obstruction and decrease in scleral permeability.[4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11] Histopathologic studies support the theory of a primary abnormality of the sclera, with secondary effects on trans-scleral protein permeability and compression of the vortex veins.

In the human eye, proteins can diffuse across the sclera, though the osmotic gradient across the sclera is near to zero with no osmotic fluid retention.[12] In 1983 Don Gass proposed that the cause of UES is impaired diffusion of protein across the sclera which results in secondary fluid retention in the suprachoroidal space.[7]

Histological studies which support Gass hypothesis show disruption and disorganization of the collagen fibers, thickening of the sclera and amorphous material expanding the space between scleral collagen fibers.[8,10,13] Another support to Gass' hypothesis was obtained by Jackson et al.[10] who demonstrated low diffusion coefficients of high molecular weight dextrans across the sclera of UES patients.

An alternative to Gass' hypothesis on the pathogenesis of UES is compression of the vortex veins by abnormally thick sclera. Yue et al.[14] reported resolution of the effusion in a patient with UES following surgical decompression of the vortex veins.

Most likely, hydrostatic forces (vortex vein compression) and osmotic forces (reduced trans-scleral protein diffusion) both cause UES, with the relative contribution of each varying in each patient with UES.[6]

Gass JD, Jallow S. Idiopathic serous detachment of the choroid, ciliary body, and retina (uveal effusion syndrome). Ophthalmology. 1982;89:1018–32.

Brockhurst RJ. Nanophthalmos with uveal effusion. A new clinical entity. Arch Ophthalmol. 1975;93(12):1989-1999.

Elagouz M, Stanescu-Segall D, Jackson TL. Uveal effusion syndrome. Surv Ophthalmol. 2010;55:134–45.

Gass JD. Uveal effusion syndrome. A new hypothesis concerning pathogenesis and technique of surgical treatment. Retina. 1983;3:159–63.

Forrester JV, Lee WR, Kerr PR, Dua HS. The uveal effusion syndrome and trans-scleral flow. Eye (Lond) 1990;4:354–65.

Stewart DH, 3rd, Streeten BW, Brockhurst RJ, Anderson DR, Hirose T, Gass DM, et al. Abnormal scleral collagen in nanophthalmos. An ultrastructural study. Arch Ophthalmol. 1991;109:1017–25.

Jackson TL, Hussain A, Morley AM, Sullivan PM, Hodgetts A, El-Osta A, et al. Scleral hydraulic conductivity and macromolecular diffusion in patients with uveal effusion syndrome. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2008;49:5033–40.

Jackson TL, Hussain A, Salisbury J, Sherwood R, Sullivan PM, Marshall J, et al. Trans scleral albumin diffusion and suprachoroidal albumin concentration in uveal effusion syndrome. Retina. 2012;32:177–82.

Bill A. Movement of albumin and dextran through the sclera. Arch Ophthalmol. 1965;74:248-252.

Gass JD. Uveal effusion syndrome. A new hypothesis concerning pathogenesis and technique of surgical treatment. Retina. 1983;3:159–63.

Forrester JV, Lee WR, Kerr PR, Dua HS. The uveal effusion syndrome and trans-scleral flow. Eye (Lond) 1990;4:354–65.

Jackson TL, Hussain A, Morley AM, Sullivan PM, Hodgetts A, El-Osta A, et al. Scleral hydraulic conductivity and macromolecular diffusion in patients with uveal effusion syndrome. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2008;49:5033–40.

Ward RC, Gragoudas ES, Pon DM, Albert DM. Abnormal scleral findings in uveal effusion syndrome. Am J Ophthalmol. 1988;106:139-146

Jackson TL, Hussain A, Morley AM, Sullivan PM, Hodgetts A, El-Osta A, et al. Scleral hydraulic conductivity and macromolecular diffusion in patients with uveal effusion syndrome. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2008;49:5033–40.

Yue BYJT, Duvall J, Goldberg MF, et al. Nanophthalmic sclera: Morphologic and tissue culture studies. Ophthalmology. 1986;93:534.

Elagouz M, Stanescu-Segall D, Jackson TL. Uveal effusion syndrome. Surv Ophthalmol. 2010;55:134–45.

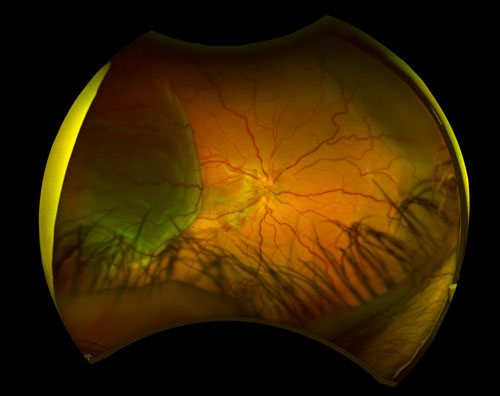

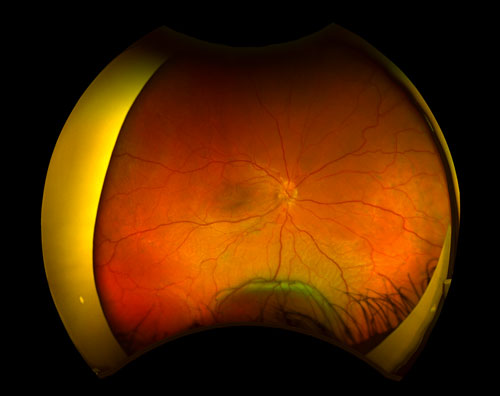

UES clinical features may vary from small peripheral elevation with preserved visual acuity to extensive detachments of choroid and ciliary body with vision loss due to involvement of the macula. Deep retinal or subretinal exudates may appear prior to the serous detachment, and optic nerve edema may be present (Figure 29.1).[4,6] UES is usually defined by a relapsing clinical course. There is usually an associated serous retinal detachment, with shifting subretinal fluid as the subretinal fluid is heavy and proteinaceous. Uveal, retinal, or vitreous inflammation is minor or absent. In chronic conditions the subretinal fluid may lead to changes in the retinal pigment epithelium (RPE) which can cause leopard-spot fundus. Nanophthalmic eyes may have associated findings, such as high hyperopia and a history of angle closure glaucoma.[2] Resolution of the fluids occurs in most patients but it may take months. or even years.[4]

Gass JD, Jallow S. Idiopathic serous detachment of the choroid, ciliary body, and retina (uveal effusion syndrome). Ophthalmology. 1982;89:1018–32.

Elagouz M, Stanescu-Segall D, Jackson TL. Uveal effusion syndrome. Surv Ophthalmol. 2010;55:134–45.

Gass JD, Jallow S. Idiopathic serous detachment of the choroid, ciliary body, and retina (uveal effusion syndrome). Ophthalmology. 1982;89:1018–32.

- Persistent Hypotony

- Multifocal, atypical, bullous central serous retinopathy

- Posterior scleritis

- Infectious or inflammatory choroiditis

- Choroidal neopla¬sia

- Choroidal metastasis

- Paraneo¬plastic syndromes

- Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada disease

- Retinitis pigmentosa

- Chronic rhegmatogenous retinal detachment

- Postoperative inflam¬mation after cryotherapy or photoco¬agulation

- Uncontrolled hypertension

UES is a clinical diagnosis and may often be misdiagnosed. The first step in UES diagnosis is ruling out other causes of exudative retinal detachment. Measurements of the patient refraction and axial length should be done although one must keep in mind that UES can occur in a non-nanophthalmic eyes.

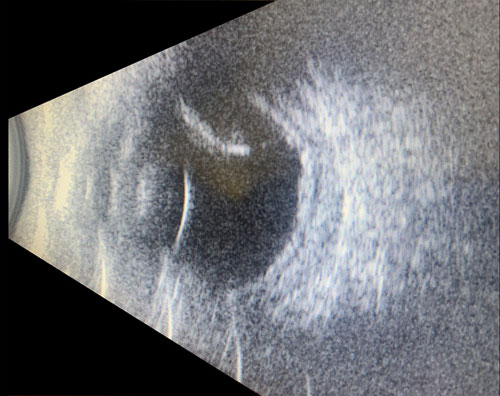

Optical coherence tomography (OCT) demonstrates subretinal fluid and focal thickening of the RPE through the leopard spots. Enhanced-depth imaging (EDI)-OCT discloses an increase in choroidal thickness and the presence of large areas of hypo¬reflectivity that may correspond to engorged choroidal veins or expan¬sion of the suprachoroidal space.[16] In the acute setting, the leopard spots will appear as hyperfluorescent on fundus autofluo¬rescence (FAF), but over time this may change to a mix of hyper- and hypo¬autofluorescence on FAF.[4,11] Fluorescein angiography in UES typically shows areas of hypofluorescence corresponding to leopard-spot pigmentation. ICG can confirm the presence of dilated choroidal vessels.[17] Ocular ultrasound should be used to measure the scleral thickness and to rule out a choroidal mass (Figure 29.3) as well as to obtain an axial length.[18] Although posterior scleral thickness greater than 2 mm is abnormal (normal value is 1 mm) and may indicate UES, recent studies showed that UES may not always be associated with an increase in scleral thickness, with mean values only 20% greater than controls in one series.[19]

Harada T, Machida S, Fujiwara T, et al. Choroidal findings in idiopathic uveal effusion syndrome. Clin Ophthalmol. 2011;5:1599-1601.

Gass JD, Jallow S. Idiopathic serous detachment of the choroid, ciliary body, and retina (uveal effusion syndrome). Ophthalmology. 1982;89:1018–32.

Jackson TL, Hussain A, Salisbury J, Sherwood R, Sullivan PM, Marshall J, et al. Trans scleral albumin diffusion and suprachoroidal albumin concentration in uveal effusion syndrome. Retina. 2012;32:177–82.

Kumar A, Kedar S, Singh RP. The indocyanine green findings in idiopathic uveal effusion syndrome. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2002;50(3):217-219.

Olsen TW, Aaberg SY, Geroski DH, Edelhauser HF. Human sclera: thickness and surface area. Am J Ophthalmol. 1998;125:237-241.

Lam A, Sambursky RP, Maguire JI. Measurement of scleral thickness in uveal effusion syndrome. Am J Ophthalmol. 2005;140:329-331

In cases where surgery is done the diagnosis can be confirmed by taking scleral biopsies to be reviewed under light microscopy and scanning electron microscopy. Staining the specimen with hematoxylin and eosin will demonstrate the disordered collagen arrangements and staining with alcian blue will identify acid mucins that are deposited in between the collagen fibers. Electron microscopy can demonstrate degenerate collagen fibrils.

Small peripheral uveal effusions may be observed, but if the serous subretinal fluid involves or threatens the fovea, then treatment is indicated. The treatment can be surgical, nonsurgical or a combination of these approaches. Since the success rate of the nonsurgical treatment is controversial and preserved for specific cases in most cases the first line of treatment will is surgical.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication which includes all images and diagrams may be reproduced, distributed, or transmitted in any form or by any means, including photocopying, recording, or other electronic or mechanical methods, without the prior written permission of the authors, except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical reviews and certain other noncommercial uses permitted by copyright law.

Westmead Eye Manual

This invaluable open-source textbook for eye care professionals summarises the steps ophthalmologists need to perform when examining a patient.